NIST Proposed an AI Standards Evaluation Framework That Pretends Attackers Don’t Exist

I submitted 33 comments to NIST GCR 26-069. The proposed AI standards evaluation framework ignores adversarial environments and will fail for security standards.

NIST released “A Possible Approach for Evaluating AI Standards Development” (GCR 26-069) on January 15, 2026. I read all 30 pages. Then I read them again, looking for the part about security. It’s not there.

The document proposes a theory-of-change methodology to measure whether AI standards achieve their goals. Sounds reasonable. The problem? The entire framework assumes a world where nobody is actively trying to break things. No adversaries. No attackers. No threat actors probing for weaknesses. Just cooperative stakeholders holding hands and measuring outcomes together.

I submitted 33 formal comments. Some of them were polite. Most of them pointed out that you can’t evaluate security standards using a methodology designed for data formatting standards. The two operate in fundamentally different realities.

This is my second formal NIST response this month. Two weeks ago, I submitted comments to the CAISI Request for Information on AI Agent Security, arguing that authorization scope matters more than human oversight for bounding agent risk. I’m starting to see a pattern. NIST asks good questions. Then, NIST proposes frameworks that miss how adversarial environments actually work. It’s exhausting.

Why This Document Made Me Write 33 Comments

I’ve spent the past year and a half contributing to the OWASP GenAI Security Project and the OWASP AI Exchange. When you’ve helped catalog threat categories for AI systems and map mitigations for each, you notice when a “comprehensive” evaluation framework ignores all of them. The OWASP Top 10 for Agentic Applications came out on December 10, 2025. It covers goal hijacking, tool misuse, identity abuse, memory poisoning, cascading failures, and rogue agent behavior. Real risks. Documented incidents.

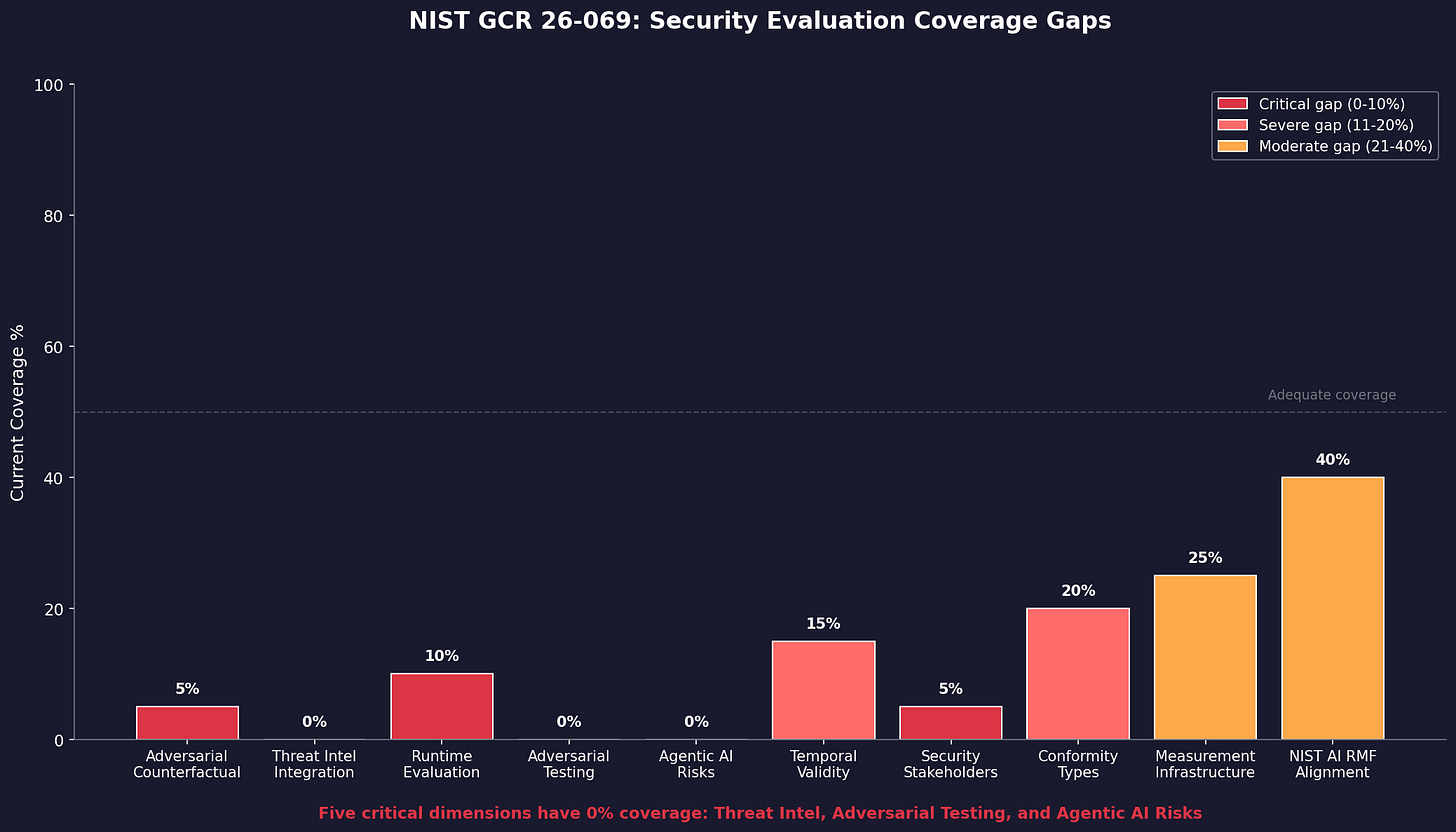

GCR 26-069 mentions none of this. Zero references to autonomous agents. Zero references to agentic AI. Zero references to multi-agent systems, tool use, or agent coordination. No MITRE ATLAS. No OWASP. No adversarial ML evaluation methods.

You know where cybersecurity experts appear in this document? Once. Buried in a list of stakeholders who might help “reduce the risks of reidentification harm.” That’s a privacy concern. Not a security concern. One mention. As an afterthought.

NIST AI 100-5, the Plan for Global Engagement on AI Standards, identifies “security and privacy” as one of six priority standardization areas. GCR 26-069 is supposed to tell us how to evaluate whether those priority standards work. A methodology that ignores adversarial environments can’t evaluate security effectiveness. It will produce conclusions that sound rigorous and mean nothing.

The timing makes this worse. EU AI Act conformity assessment kicks in August 2026. prEN 18286, the first harmonized standard for AI, entered public enquiry in October 2025. These standards will shape global AI governance. We need evaluation frameworks that actually work for security. This one doesn’t.

The Counterfactual Fantasy

The document loves counterfactual analysis. Box 5 asks: “What would have happened in the alternative state of the world?” For data integration standards, the example used throughout the entire document, this makes sense. You compare outcomes with and without the standard. The underlying process is stable. Apples to apples.

Security doesn’t work that way. Attack rates depend on attacker motivation. Attacker motivation changes when defenses change. You reduce vulnerability in Area A; attackers move to Area B. This is called attack displacement. It’s been documented for decades. Any security professional who’s worked an incident knows this.

Traditional “treatment vs. control” experimental designs fail for security because the control group isn’t static. The adversary adapts. That’s what adversaries do. It’s literally in the name.

Let me make this concrete. You want to evaluate whether an AI security standard reduced incidents. You compare incident rates before and after adoption. Incidents dropped 40%. Victory? Maybe. Or maybe attackers moved to organizations that didn’t adopt the standard. Or they pivoted to attack vectors that the standard doesn’t cover. Or they’re waiting. Attackers are patient when they need to be.

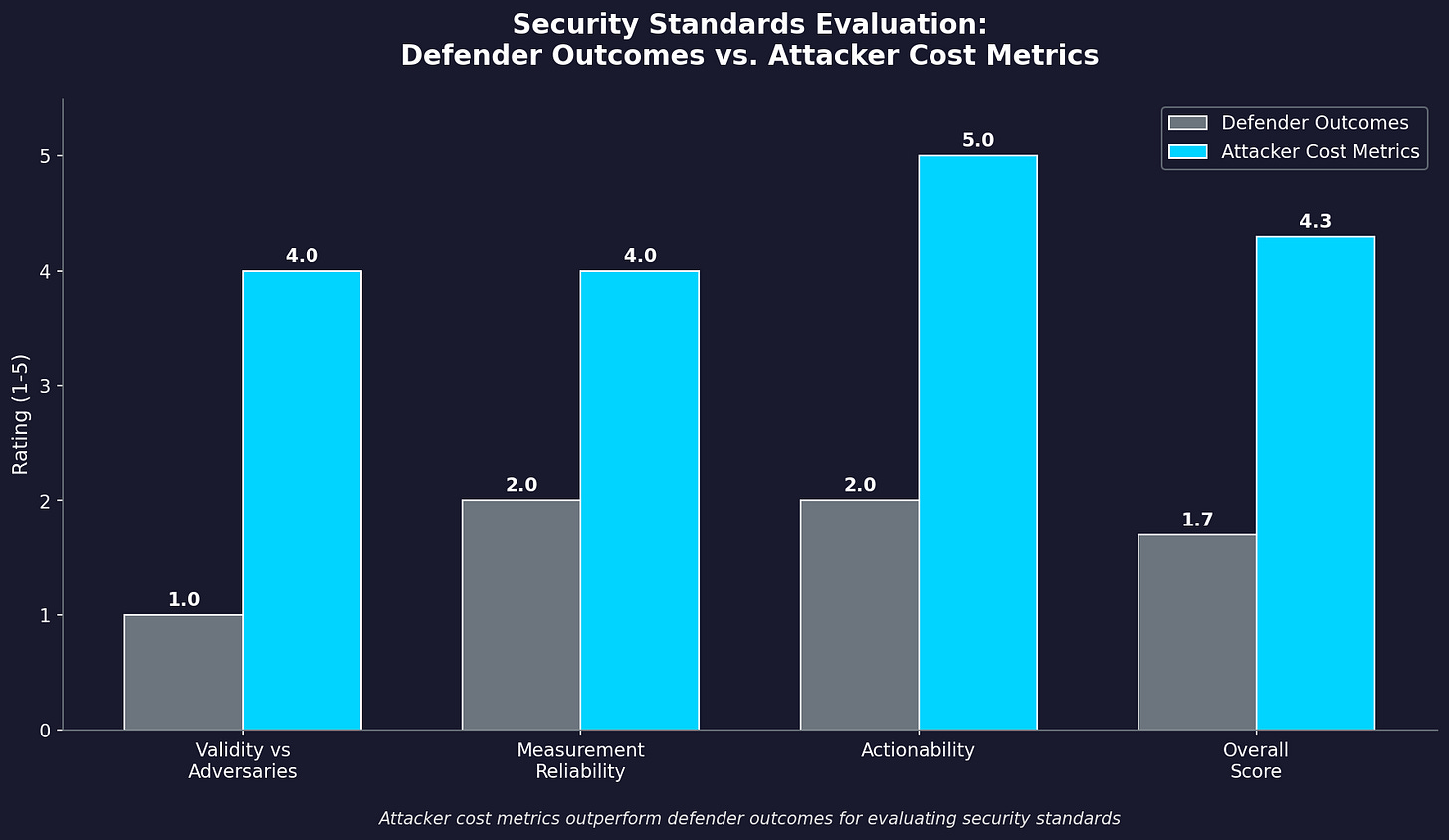

Measuring defender outcomes in adversarial environments produces garbage data dressed up as insight. The framework should measure attacker cost instead. Time-to-compromise increases. Skill threshold required to succeed. Attack surface reduction. Exploit chain complexity. These metrics sidestep the adaptation problem. Even if attackers shift targets, a standard that increases the cost to attackers has demonstrable value.

I proposed adding “Box 5a: Security Counterfactual Considerations.” Apparently, we need to spell out that a security evaluation requires considering attackers.

Process Theater vs. Actual Effectiveness

The document draws a pretty arrow from standards development activities to societal goals. Inputs lead to activities. Activities produce outputs. Outputs generate outcomes. Outcomes achieve goals. It’s a nice diagram. It’s also conflating two completely different questions.

Question one: Did the standards development organization run a good process? Were inputs adequate? Were activities effective? Did outputs ship on time? These evaluate process.

Question two: Does the standard actually work when deployed? Does it reduce harm? Does it resist adversarial exploitation? Does it hold up when someone motivated tries to break it?

These require different methodologies. Different data. Different expertise. Different timeframes. The document mostly focuses on question one while claiming to address question two.

A standard can emerge from a flawless SDO process and still fail operationally. The threat landscape evolved. The attack techniques changed. The assumptions embedded in the standard no longer match reality. Process success doesn’t guarantee effectiveness. Anyone who’s watched a beautifully documented policy get shredded by a real incident understands this.

Security effectiveness requires continuous measurement of deployed systems. Runtime outcomes. Incident response metrics. Vulnerability management data. Threat detection rates. The static theory-of-change model can’t capture any of this. It’s a snapshot methodology applied to a moving target.

I proposed adding an “Operational Feedback Loop” connecting runtime observations back to standards development. Make it iterative instead of linear. Acknowledge that the world changes between when you write a standard and when you evaluate it.

Where’s the Red Team?

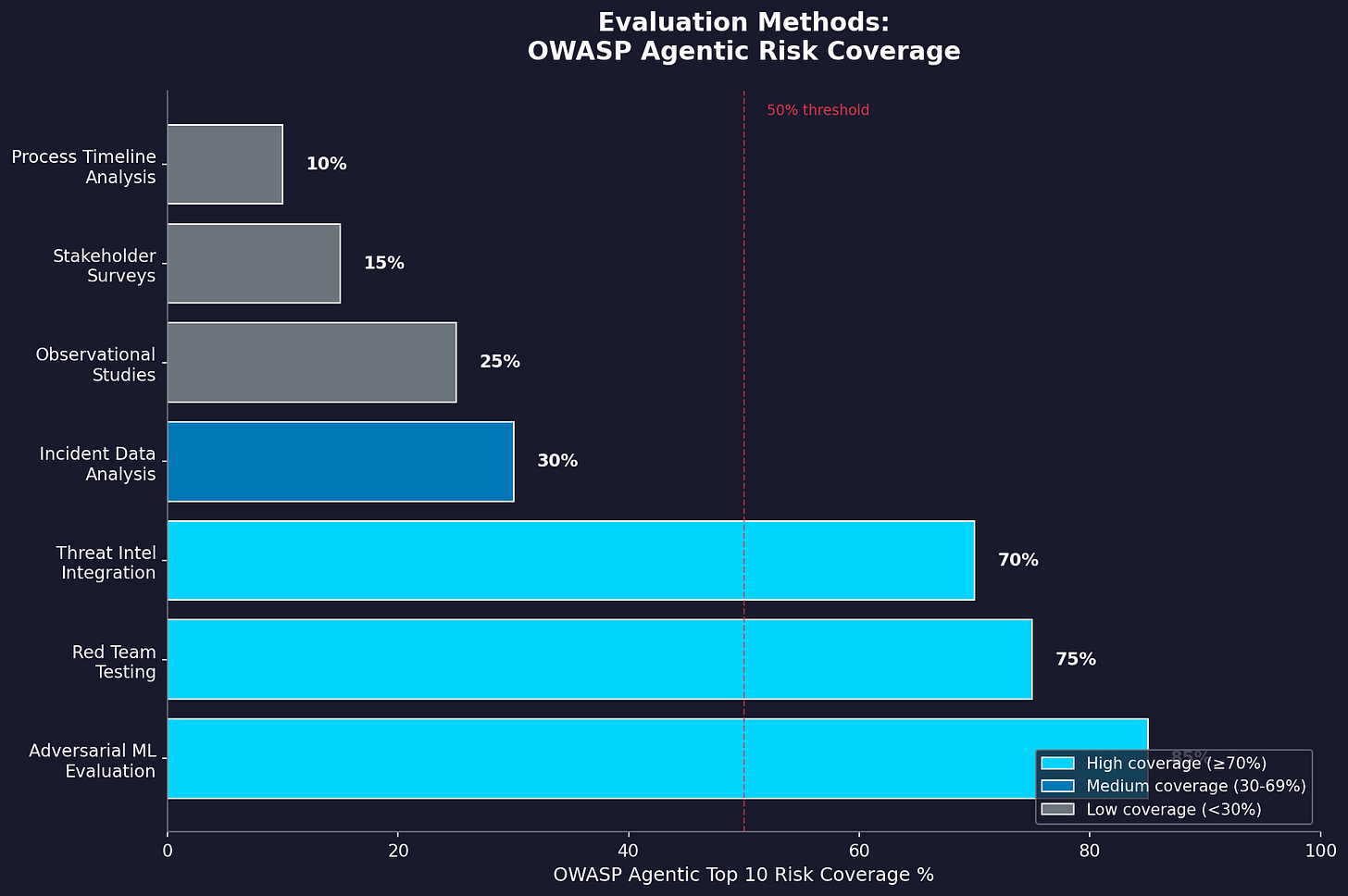

The evaluation methodology relies on observational studies, stakeholder surveys, and outcome measurement. For security standards, this is like checking whether a lock works by asking people if they feel safe.

You can survey organizations about their security posture. You can measure incident rates. Neither tells you whether the standard defends against the threats it claims to address. You’re measuring perception and lagging indicators. You’re not measuring actual resistance to attack.

Adversarial testing fills this gap. Red teaming. Penetration testing. Adversarial ML evaluation. These methods actively probe for weaknesses rather than waiting for someone to exploit them. The ICLR 2025 research on AI safeguards found that defenses “often fail against novel attack methods not seen during development.” Minor changes to attack parameters produce dramatically different success rates. Static evaluation misses all of this.

For security-related standards, evaluation should include a red-team assessment of implementations, penetration testing against compliant systems, adversarial ML evaluation using MITRE ATLAS techniques, and comparisons between compliant and non-compliant implementations. This provides direct evidence. Not surveys. Not feelings. Evidence.

The OWASP Top 10 for Agentic Applications offers a ready-made threat taxonomy. Goal hijacking resistance (ASI01). Tool misuse prevention (ASI02). Identity and privilege abuse controls (ASI03). Supply chain integrity (ASI04). Memory poisoning resistance (ASI06). Ten documented risk categories with real incidents behind them. Standards can be evaluated against these attack patterns. We don’t have to wait for the next breach to find out if the standard works.

Validity Problems Nobody Mentioned

Section 2.2 discusses internal validity, construct validity, self-selection bias, and external validity. Standard methodology considerations. All framed for benign interventions where nobody is trying to make you fail.

Security standards face validity threats that the document doesn’t acknowledge…

Adversarial adaptation breaks your baseline. The baseline isn’t stable because attackers respond to defenses. Every security measurement includes this noise.

Security metrics are garbage. Organizations detect and report a fraction of actual intrusions. Your denominator is wrong. Your numerator is wrong. Your confidence interval should be a shrug emoji.

The counterfactual is unobservable. “What would attackers have done?” isn’t something you can measure. You can’t run a controlled experiment on motivated adversaries. They don’t fill out consent forms.

Temporal validity fails fast. A standard effective against 2024 attack techniques may be useless against 2026 techniques. MITRE ATLAS regularly adds new adversarial ML techniques. How long does a security standard remain effective? The framework doesn’t ask.

These aren’t minor gaps. There are fundamental problems with applying this methodology to security standards. The framework needs security-specific validity guidance, or it will produce findings that look rigorous and mislead everyone who reads them.

What I Told NIST

My 33 comments include specific recommendations. Not just complaints. Fixes.

First, add a security-focused illustrative example. The document uses data integration throughout. Fine. Add a parallel example, such as “Autonomous Agent Credential Management,” that walks through the same structure with security-centric measures. Show how security inputs differ (threat intelligence, red team findings, incident data). Show security-specific activities (adversarial testing, penetration testing). Show security outputs (threat coverage matrices, attack resistance specifications). Show security outcomes (attacker cost increase, exploit chain complexity). Show security goals (adversarial robustness, resilience under attack). Make the framework demonstrate that it can handle security. Don’t just assume it.

Second, add Adversarial Evaluators as a stakeholder category. Traditional stakeholder engagement assumes cooperative participants seeking shared outcomes. Security evaluation requires people who deliberately adopt attacker mindsets. Red team operators. Penetration testers. Adversarial ML researchers. Threat intelligence analysts. Their value comes from challenging consensus, not building it. That’s how you formally integrate adversarial perspectives.

Third, distinguish voluntary from mandatory conformity outcomes. The EU AI Act creates a binary measure: whether an AI standard meets the “presumption of conformity” under Article 40. This should be an explicit evaluation criterion. Voluntary conformity exhibits self-selection bias. Mandatory conformity creates natural experiments. Different mechanisms. Different evaluation approaches.

Fourth, specify measurement infrastructure requirements. Security evaluation requires telemetry from deployed systems, threat intelligence feeds, vulnerability databases, and incident reporting mechanisms. Without this infrastructure, security outcomes are unmeasurable. The document should specify which data-collection capabilities are prerequisites for meaningful evaluation. Otherwise, people will try to evaluate security standards without the data needed to do it.

Key Takeaway: This framework will produce misleading conclusions about security standards because it ignores adversarial adaptation, conflates process with effectiveness, and lacks a methodology for measuring what actually matters: whether standards increase the cost to attackers.

What to do next

If you’re responsible for AI security standards adoption, don’t confuse compliance with security. A standard that emerged from a rigorous SDO process can still fail operationally if threats evolved since publication. Build your own threat-informed evaluation. Don’t trust process-focused assessments to tell you whether you’re actually protected.

For organizations building AI governance programs, the CARE Framework provides structured risk assessment that accounts for adversarial considerations. The RISE Framework addresses organizational readiness for the continuous evaluation that AI security demands.

NIST welcomes feedback on GCR 26-069 via email to ai-standards@nist.gov. They’re planning an online event to discuss the approach. The CAISI AI Agent RFI comment period runs through March 9, 2026. If you haven’t read my analysis of why authorization scope beats human oversight for agent security, the arguments connect to what I’ve outlined here. Both documents share the same blind spot.

More security practitioners need to engage with these processes. Otherwise, NIST guidance will reflect the views of people who’ve never had to defend a production system against a motivated attacker.

👉 Subscribe for more AI security and governance insights with the occasional rant.

👉 Visit RockCyber.com to learn more about how we can help you in your traditional Cybersecurity and AI Security and Governance Journey

👉 Want to save a quick $100K? Check out our AI Governance Tools at AIGovernanceToolkit.com

Exceptional breakdown of how static evaluation frameworks collapse under adversarial pressure. The attacker cost metrics argument is spot-on, measuring defender outcomes when adversaries adapt is measuring noise not signal. Submitted formal comments to similar NIST frameworks last year and ran into this exact blind spot where processs rigor gets mistaken for operational efectiveness.